How to write a Constrained Identity Function (CIF) in TypeScript

A handy advanced TypeScript pattern to increase your productivity.

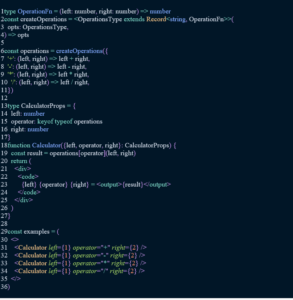

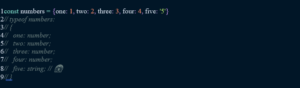

In How to write a React Component in TypeScript, I typed an example React component. Here’s where we left off:

I’m not satisfied with the operations function though. I know that every function in that object is going to have the exact same type (by necessity due to the use case):

I’m not satisfied with the operations function though. I know that every function in that object is going to have the exact same type (by necessity due to the use case):

![]()

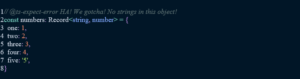

The operations object is really just a record of operation strings mapped to a function that operates on two numbers. So if we add a type annotation on our operations variable, then we don’t have to type each function individually. Let’s try that:

Sweet, so we don’t have to type every function individually, but oh no… now the typeof operations is Record<string, operationfn=””> and the keyof of that is going to be string which means our CalculatorProps[‘operator’] type will be string. Ugh 😩

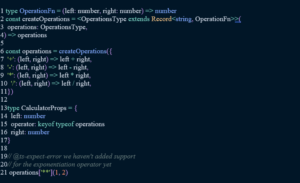

Here’s what we could do to fix this:</string,>

But now we’re back to having to add ** in two places if we decide to add the Exponentiation operator. However, in this case, TypeScript will give us a compiler error if we add it in one and not the other, so that’s a step up.

This is where I left this when I first wrote this component, but then @AlekseyL13 suggested that I try a properly typed identity function.

The constrained identity function

First, let’s keep in mind, we have 2 goals:

1. Enforce that the type of each property is the same (in this simple example, it’s just a number, but in our actual example, it’s a function type)

2. Ensure that keyof typeof for our object results in a finite union of the keys

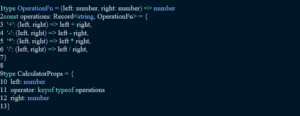

With TypeScript, it’s a challenge to have both of these. By default, we get the second goal. The problem is that when you try to accomplish the first goal with a type annotation like const operations: Record<string, operationfn=””> = …, you end up widening the key so keyof typeof results in string. Ugh, how annoying.

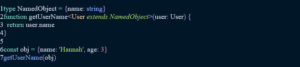

So here’s where the constrained identity function comes in. By the way, “constrained” describes a situation where you have a function that accepts a narrower version of an input than it’s passed.Here’s a simple example:</string,>

So the object that’s passed to getUserName must satisfy all the types in the NamedObject. The getUserName constrains the input to at least match that type.

And an “identity function” is a function that accepts a value and returns that value. I sometimes use these kinds of functions as the default value for callbacks:

So with those definitions out of the way, a “constrained identity function” is a function which returns what it is given and also helps TypeScript constrain its type. This is exactly what we want to do.

We can call it a CIF (pronounced “see eye eff”). Sure, let’s go with that.

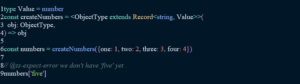

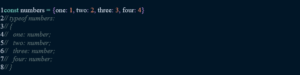

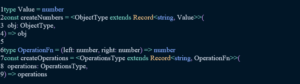

Let me show you a simple example first, then I’ll explain what’s going on, then we can apply it more usefully to our more complicated example:

So the createNumbers is the constrained identity function. It returns the obj it’s given, hopefully that’s clear. But how does it enforce our input and constrain the type?

Let me explain it this way. If we start with:

But in the future, someone could come to this code and change it like this:

Yikes! Nah, we can’t have that! (And, more importantly, in our Calculator example, some auto-typing on the functions is the goal here).

So, let’s enforce our value types with a type annotation:

ut now by typing our values explicitly, we’ve told TypeScript that our key can be a string. Unfortunately, there’s no way to tell TypeScript: “This thing has the keys it has, but the values are this specific type.” IMO, this is a missing feature of TypeScript. Our createNumbers constrained identity function (er… “CIF”) is a workaround.

So here’s what that workaround is:

Constrained identity functions allow us to not explicitly annotate our variable while still getting to enforce the values.

So we create the object, get the best type that TypeScript can offer us (which includes the narrow keys and wide values), then we pass it to a function which accepts wide keys and narrow values. TypeScript combines that to give us a Record with a key and value which are both narrow!

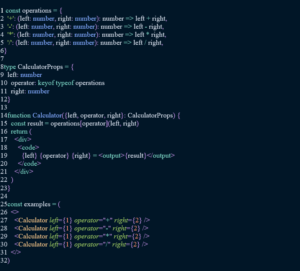

Alrighty, so let’s apply a CIF to our original situation:

Wahoo! So with this solution we don’t have to explicitly type all the operation functions the exact same way and we can still get a union type of all available operations.

Wahoo! So with this solution we don’t have to explicitly type all the operation functions the exact same way and we can still get a union type of all available operations.

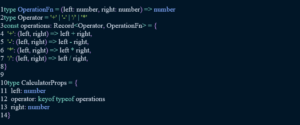

A generic CIF?

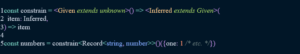

You may have noticed that we had two CIFs in the previous section:

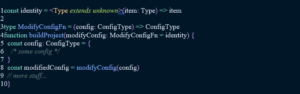

Wouldn’t it be neat if we could combine those? Sure would. But you’re not going to like it… Here’s what I tried first:

![]()

Sad day. Unfortunately this is just not possible with TypeScript today. But here’s a workaround:

.. yeah, I told you you wouldn’t like it. It’s marginally better like this:

![]()

But like, huh. Bummer.

Luckily, I don’t find myself making CIFs very often anyway and they aren’t difficult to write so I don’t need an abstraction for them. Thought it’d be interesting to share with you though 😄

Conclusion

Here’s the final version of our calculator component with everything typed with our CIF: